Having recently had an opportunity to do some green screen work, which at first glance seemed to be a quick job, and later turned out to require some pretty hefty rotoscopy and compositing, I decided to write down another caveat, this time on using a green screen. Please note, that the pictures are for illustrative purposes only. For convenience, wherever they are labelled as YCbCr colorspace, I used Photoshop Lab/YUV to create them, which is very similar, but not identical to YCbCr. Also, many devices use clever conversion and filters during chroma subsampling, which reduces aliasing and generally are better at preserving the detail, than Photoshop is in its RGB->Lab->RGB conversion, so the loss of detail and differences might be a little smaller, than depicted here, but are real nevertheless.

Green screen mostly came about because of the way that digital camera sensors are built. The most common bayer pixel pattern in CMOS sensors used by virtually all single-chip cameras consists of two green sensors, and a single blue and red ones (RGGB). Which is a sensible design, if you consider the fact that the human eye is the most sensitive in green-yellowish regions of the light spectrum. It also means, that you will automatically get twice as much resolution from the green channel of a typical single-chip camera, than from either red or blue one. Add to this the fact that the blue sensors most often have the most noise, due to the fact that the blue light has the least energy to deposit in a sensor, and the signal is simply the lowest there, and you might start to get a clue why green screen seems to be such a good idea for digital acquisition.

Typical CMOS RGGB pixel mosaic. There are two times as many green pixels than red or blue.

So far this discussion did not concern 3-sensor cameras or the newest Canon C300 with the sensor twice the size of encoded output, however the next part does.

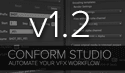

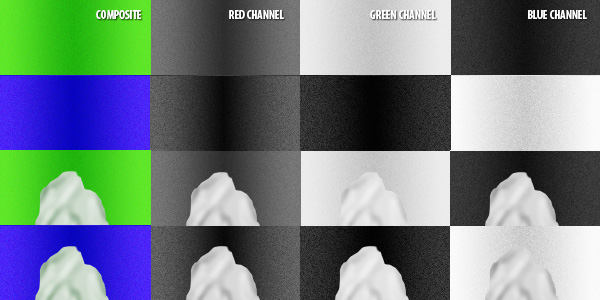

Green channel has the most input (over 71% in Rec 709 color space specification) in the calculated luma (Y) value, which is most often the only one that gets encoded at full resolution when compression scheme called chroma subsampling is used – which is almost a given in most cases. All color information is usually compressed in one way or another. In 4:2:0 chroma subsampling scheme – common to AVCHD in DSLRs and XDCAM EX – the color channels are encoded at 1/4th of their resolution (half width and half height), and in 4:2:2 at half resolution (full height, half width). These encoding schemes were developed based upon the observation that a human eye is less sensitive to loss of detail in color than in brightness, and in horizontal plane, than in vertical. Regardless of how well they function as delivery codecs (4:2:2 is in this matter rather indistinguishable from uncompressed), they can have serious impact on compositing, especially on keying.

Graphical example of how various chroma subsampling methods compress color information

Recording 4:4:4 RGB gives you an uncompressed color information, and is ideal for any keying work, but it is important to remember, that you won’t get more resolution from the camera, than its sensor can give you. With typical RGGB pattern, and sensor resolution not significantly higher, than final delivery, you will still be limited by the debayering algorithm and the lowest number of pixels. It’s excellent if you can avoid introducing compression and decompression artifacts, which will inevitably happen with any sort of chroma subsampling, but it might turn out that there is little to be gained in pursuing 4:4:4 workflow due to the lack of proper signal path, as is for example with any HDMI interface from DSLRs, which outputs 8-bit 4:2:0 YCbCr signal anyway, or many cameras not having proper dual-link SDI to output digital 4:4:4 RGB. Analog YCbCr output signal (component) is always at least 4:2:2 compressed.

A good alternative to 4:4:4 is a raw output from camera sensor – provided that you remember about everything what I wrote before about the actual sensor resolution. So far there are only two sensible options in this regard – RED R3D and ArriRaw.

There are also not very many codecs and acquisition devices that allow you to record 4:4:4 RGB, and most still require fast and big storage arrays, and thus its application is rather limited to bigger productions with bigger budgets. It is slowly changing due to falling prices of SSD drives that easily satisfy the writing speed requirements, and portable recorders like Convergent Design Gemini, but storage space and archiving of such footage still remains a problem, even in the days of LTO-5.

Chroma subsampling introduces artifacts that are mostly invisible to the naked eye, but can make proper keying hard or even impossible

Readers with more technical aptitude can consult two more detailed descriptions of problems associated with chroma subsampling:

- Merging computing with studio video: Converting between R’G’B’ and 4:2:2

- Towards Better Chroma Subsampling

The higher sensitivity of human eye and cameras to green color means also, that you don’t need as much light to light the green screen, as you would for the blue one. The downside however is that the green screen does have much more invasive spill, and due to the fact that it is not a complementary color to red, it is much more noticeable and annoying than the blue spill, and requires much more attention during removal. Plus spending a whole day in a green screen environment can easily give you a headache as well.

Generally it is understandable why the green screen is a default choice for digital pipeline. However, as with all rules of the thumb, there is more than meets (or irritates) the eye.

When considering keying, you need to remember that it is not enough that you get the highest resolution in the channel where your screen is present (assuming that it is correctly lit, does not spill into other channels, and there is not much noise in the footage). Keying algorithms still rely on contrasting values and/or colors, using separate RGB color channels. Those channels – if chroma subsampled – are reconstructed from YCbCr in your composition software.

Therefore, even assuming little or no spill from the green screen to the actors, if you have a gray object (let it be a shirt), which has similar value in green channel to the green screen, then this channel is made useless for keying by this very fact. You can’t get any contrast from it. You and your keying algorithm are left to try obtaining the proper separation in the remaining channels, first red, and then blue (where most likely most of the noise resides, and which has meager 7% input in luminance), which automatically reduces your resolution, also introducing more noise. In the best case you get a less crispy and a little unstable edge. In the worst, you have to resort to rotoscoping, defeating the purpose of shooting on the green screen in the first place.

Now consider the same object on a blue screen – when your blue screen has the same luminance as a neutral object, then you throw the blue channel away, and most likely can use green and red channels for keying. Much better option, wouldn’t you say?

If the green value of an object on a green screen is similar to the screen itself, keying will be a problem

Of course this caveat holds true only for items with green channel level close to the level of the screen. If we want to extract shadows, it’s a completely different story – we need to get contrast in the shadows as well, and to this end green screen will most likely be more appropriate. But if we don’t, then choosing a color of the screen entails more than simply looking what color the uniforms or props are or a basic rule of the thumb that “green is better for digital”. You need to look at the exposure as well.

There are a few other ways to overcome this problem. One is to record 4:4:4 using a camera that can deliver proper signal, then you are only limited by the amount of noise in each channel. Another is to shoot at twice the resolution of final image (4K against 2K delivery), and then to reduce the footage size before keying and compositing. This way the noise will be seriously reduced, and the resolution in every channel will be improved. Of course, then it is advisable to output the intermediates to any 4:4:4 codec (most VFX software will make excellent use of DPX files) to retain the information.

Another sometimes useful – and cheap – solution might be to shoot vertically (always progressive, right?), thus gaining some resolution, however remember that in 4:2:2, and in 4:1:1 compression schemes, it is the horizontal (and now vertical) resolution that gets squashed, so the gain might not be as high as you hoped, and in the dimension that is more critical for perception, so make sure that you’re not making your situation worse.

The key in keying is not only to know what kind of algorithm or plugin to use. The key is also to know what kind of equipment, codec and surface should be used to obtain the optimal results, and it all starts – as with most things – even before the set is build. Especially if you’re on a budget.

To sum up:

- Consult your VFX supervisor, and make sure he’s involved throughout the production process.

- Use field monitoring to see how the exposition in the green channel looks like, and if you are gettting proper separation.

- Consider different camera and/or codec for green/blue screen work.

- Try to avoid chroma subsampling. If it’s not feasible, try to get the best possible signal from your camera.

- Consider shooting VFX scenes in twice the final resolution to get the best resolution and the least noise.